How Bristol research confronted worker exploitation in electronics manufacturing

Better migrant workers’ rights at the world’s biggest consumer electronics manufacturer, thanks to study which highlights the effects of ‘just-in-time’ manufacturing on staff

New Asian electronics plants in Europe

Alarm bells rang in the early 2000s when a host of Asian electronics firms set up manufacturing plants in Europe.

“Electronics manufacturing has a notorious reputation for poor working conditions,” explains Dr Rutvica Andrijasevic of the University of Bristol Business School.

“We have good evidence from China of exploitation of workers, low unionisation and authoritarian labour relations in many of these huge electronics multinationals.”

“This was why trade unions and NGOs were so concerned when some of these firms opened factories in central and eastern European countries like Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary. How would they treat their new workers?”

Investigations in Czechia

Among the companies to expand into Europe was Foxconn, the world’s biggest consumer electronics manufacturer. Headquartered in Taiwan, it is perhaps best known – and highly scrutinised – for assembling Apple products at its Chinese plants.

For Andrijasevic, whose research focuses on migrant workers, it was hugely important to explore the employment conditions at Foxconn’s new plants, where around half of workers are recruited from around the world.

Together with colleagues from the University of Hong Kong and the University of Padua, Andrijasevic travelled to Czechia throughout 2014ꟷ2017 to investigate employment practices at two Foxconn factories.

Staying alongside factory workers in their employer-provided dormitory, the research group were able to get a near first-hand picture of working life at the Czechian plants.

A multi-national workforce

They undertook an extensive series of interviews with 23 nationalities of factory workers, a colossal task that took an army of interpreters to overcome language barriers.

These workers had come to Czechia from a range of fellow former Communist countries, including Ukraine, Mongolia, Romania, Bulgaria and Vietnam. They were employed not by Foxconn, but by temporary work agencies who satisfy manufacturers’ fluctuating labour needs by loaning out staff according to shifting demand on the production line.

Other interviewees who played a valuable part in the study included the dormitory’s resident hairdresser who, naturally, “knew everyone and everything. I realised I had made a basic mistake by not speaking to her earlier.” To the researchers’ delight, Foxconn themselves also agreed to be interviewed – after much initial hesitation.

“For a long time, we repeatedly asked Foxconn management for an interview, but they kept saying ‘no’,” Andrijasevic explains. “But then one day, while we were doing research on Foxconn’s subsidiary in Turkey, their second-in-command suddenly got in touch and said, ‘I want to give my story.’ We were thrilled.”

Exploitation

The study provided the first data on employment conditions in Asian electronics’ plants in Europe. Despite national, EU and UN labour regulations to protect workers, it emerged that the temporary migrant workers were subject to exploitative working and living conditions by the temporary work agencies (discussed in Andrijasevic & Sacchetto, 2017).

Non-payment of wages, illicit deductions from pay, and deception over hours and conditions of work by the temporary work agencies were just some of the issues revealed by the interviews. Female workers who fell pregnant were illegally dismissed and risked deportation to their home country.

Workers faced the risk of homelessness due to the tied accommodation, which often provided sub-standard living conditions and were places where women felt particularly uncomfortable. “Women just had to muster all their courage to go and shower as there were no locks on the doors. They had to share toilets with the men too,” says Andrijasevic. “I saw a real lack of safety and privacy in the dorms. I didn’t dare use the showers myself during my stay.”

Electronics Watch

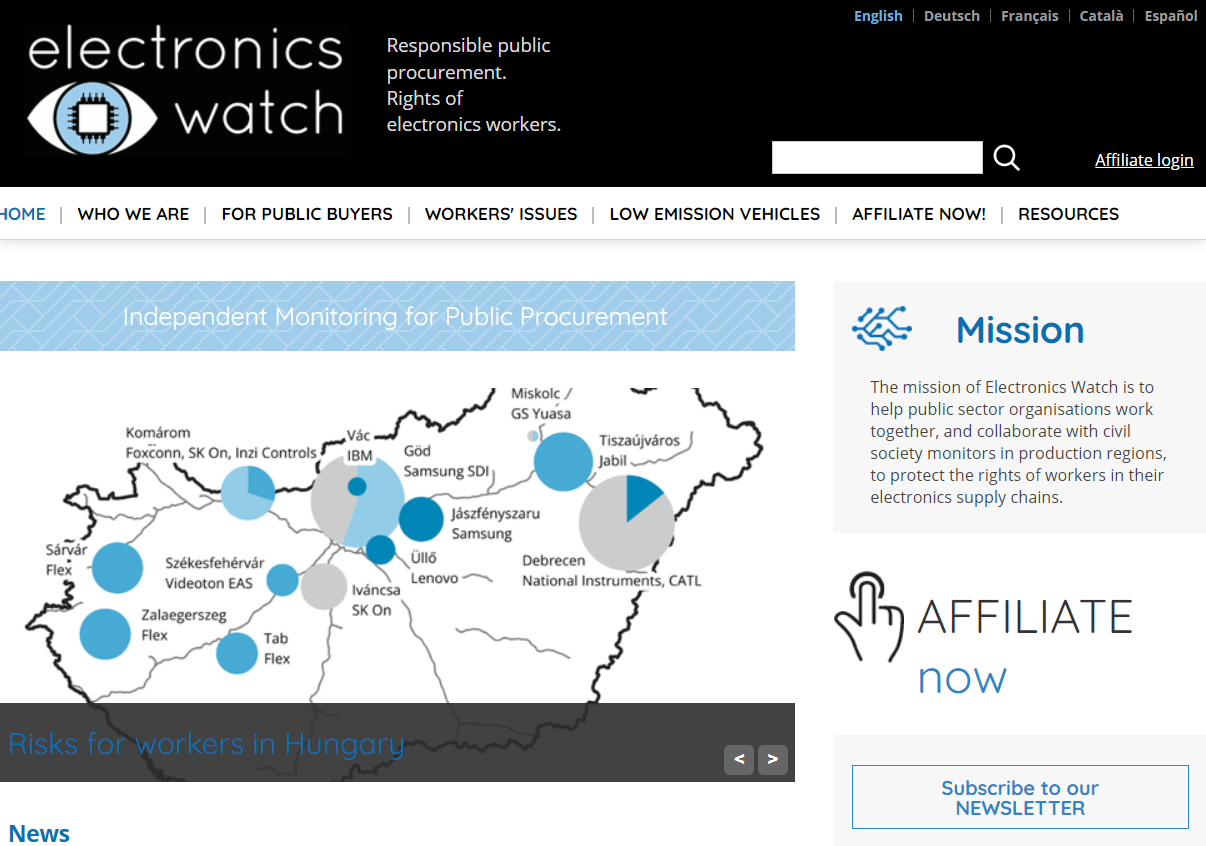

The study caught the attention of Electronics Watch, a leading third sector organization that helps public sector buyers (governments, local authorities and universities) to purchase ICT hardware from firms that comply fully with domestic and international labour rights.

Electronics Watch recruited two members of Andrijasevic’s research team to conduct two in-depth studies of Foxconn’s management practices in Czechia. Drawing heavily on Andrijasevic’s initial research findings, Electronic Watch’s studies (2016 and 2017) concluded that Foxconn was indeed in breach of Czech Labour Code.

Consequently, Electronics Watch and Andrijasevic continued their collaboration and examined the risk to workers in electronics assembly in Hungary. The final report, published in 2022, provides recommendation on key actions to mitigate those risks.

Hewlett Packard audit

A major turning point in Electronics Watch’s campaign to improve conditions for Foxconn’s workers in Czechia came in 2017 when Hewlett Packard conducted a systematic external audit of the plants that assessed working conditions including, for the first time, those for the temporary agency workers.

Triggered by the two reports, the audit was especially significant given that Hewlett Packard are Foxconn’s main customer in Europe. While they felt that the dormitories fell outside of their jurisdiction, their audit agreed that living conditions for the 5,000-6,000 tenants were sub-standard.

Improved living conditions and workers’ rights

The audit prompted a number of positive changes. First, Foxconn established a Compliance & Development Office in 2018 to improve working conditions by supporting foreign workers’ with their concerns, whether relating to their time on the production line or their private needs off-work, such as through better safety at work and access to health and schooling services.

Living conditions in one of the dormitories also improved. This was refurbished and upgraded to address the former lack of privacy and cleanliness and provide basic standards, such as hot water and separate showering facilities for male and female workers. “This may be only one dormitory,” says Andrijasevic, “but it’s a good start. I hope the improvements will be rolled out across all the dorms.”

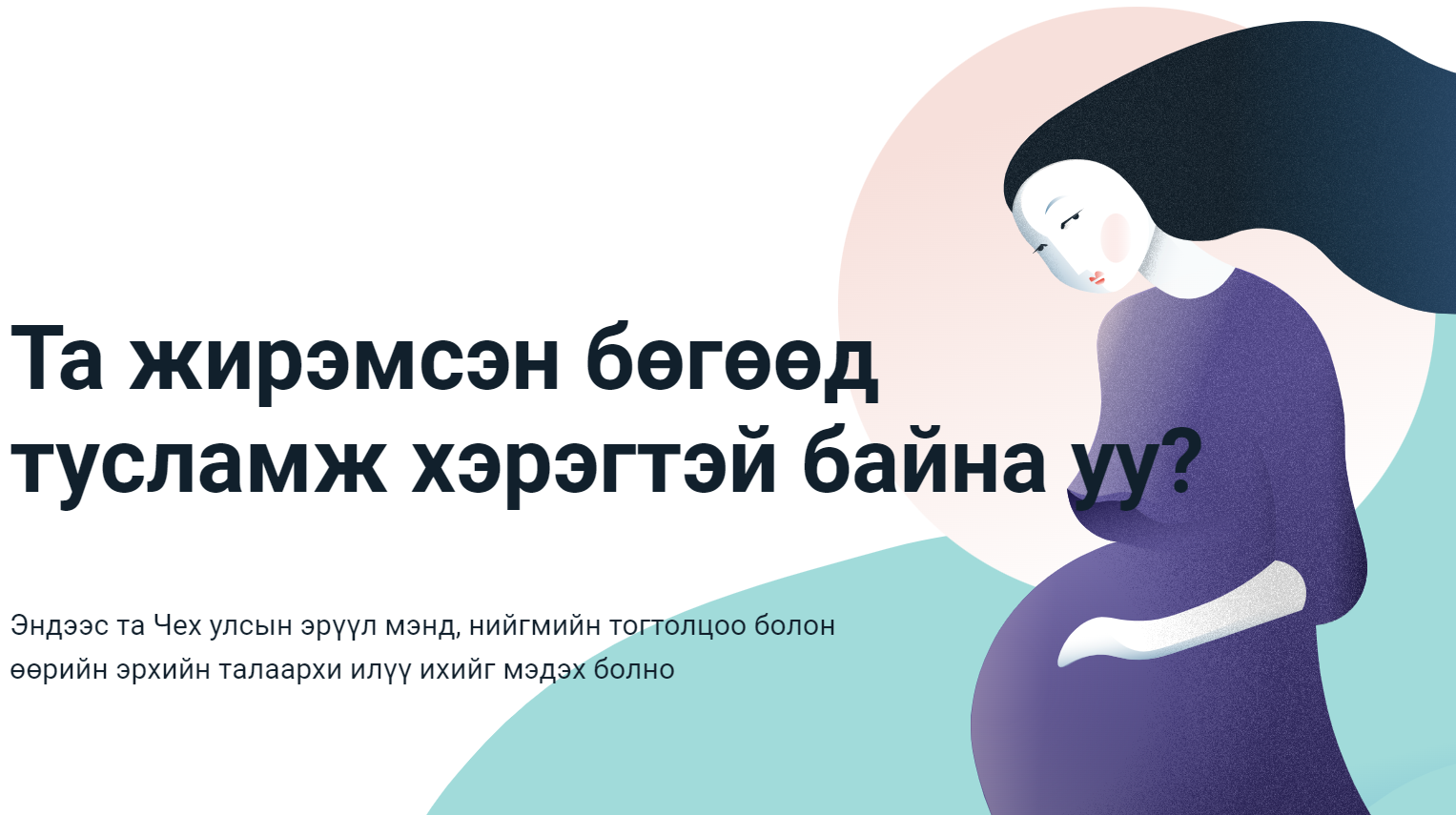

Andrijasevic also ensured that pregnant women were given more support. Collaborating with two local NGOs, Multicultural Centre Prague and Most Pro, she produced a website and leaflet in 2018, Pregnant and in need of advice?. Translated into Mongolian, Ukrainian, Russian, English and Czech, these inform women of their rights, and health and social security entitlements.

“The website and leaflet have had a great impact,” Andrijasevic explains. “Most Pro have told me that foreign women workers are more informed about their labour and social rights, and are feeling more empowered.”

“Recently, there was a case where a pregnant woman even challenged HR over her dismissal and retained her job.”

Further striving to improve workers’ conditions throughout the wider electronics industry, Andrijasevic and Electronics Watch led a training session for managers of electronics firms better safeguard temporary migrant workers.

An important boost to workers’ rights the world over came in 2021 when Electronics Watch and the Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), the world’s largest industry coalition dedicated to ethical practices in global supply chains, entered into a formal agreement to address issues with working conditions throughout the global electronics supply chains of RBA members where products are manufactured for public procurement. This significant move was instigated by the findings of Hewlett Packard’s 2017 audit of Foxconn’s Czech plants.

‘Just-in-time’ labour

For Andrijasevic, the conditions at the Czech plants are symptomatic of wider, systemic issues in manufacturing. Specifically, the disposable workforce provided by the temporary work agencies is a product of the ‘just-in-time’ manufacturing model (see: Sachetto & Andrijasevic, 2016).

Pioneered by the car manufacturer Toyota in the 1970s, the just-in-time management system, also known as ‘lean manufacturing’, has since been widely adopted by many industries around the world. Prioritising efficiency by ordering in production parts and materials only as required by the rapidly changing production schedule, its mode of thinking has spilled over into staffing.

“The just-in-time manufacturing model hinges on just-in-time labour,” says Andrijasevic. “Electronics is organised on an on-demand basis, it’s a seasonal model.

“When a new product is launched, for instance, there may be a tight deadline of one month for production. Temporary staff are brought in to cover the increased workload, and then let go once it’s done.”

“The manufacturers don't want to hire the staff directly because it entails too much work in this peaks and troughs system.”

One Polish worker, when interviewed as part of a preliminary study, explained some of the realities of this working lifestyle: “Last month I only worked 51 hours and I made 3,000 Koruna (€120). I went to the factory every morning to see if there was work, but they said that there was nothing for me. There were a few hundred of us, but the boss only called about ten people so the rest of us just went back to our dormitory.”

Indeed, Andrijasevic’s research finds that the dormitories play a pivotal role in facilitating the just-in-time model of production by providing a stationary ‘on tap’ workforce.

She’s particularly concerned that workers’ private lives are colonised through the dormitory accommodation: “Workers’ family lives, even whether they date anyone, are controlled by the model,” says Andrijasevic. “The model says ‘we only want single workers’. Even if you have a partner and kids, the kids can’t be in the dormitories”.

Future outlook

The effects of dormitories on workers’ private lives are something that Andrijasevic is exploring in follow-on research. To reduce exploitation of migrant workers, Andrijasevic argues that electronics firms must reduce their reliance on temporary work agencies.

“That said, what has been achieved at Foxconn’s Czech plants through coordinated efforts and hard work is fantastic. I just hope that this can be replicated more widely. Removing temporary work agencies would be removing a huge obstacle to better rights for the migrant workers.”