Housewife or space engineer? Gender norms and life outcomes

What children’s essays from 1969 can teach us

The research

Despite advancements in gender equality, women still face disparities in earnings compared to men. One of the many reasons for this are traditional gender norms which suggest that women are primarily responsible for child-rearing and home-making.

But why do some women conform more with stereotypical gender norms and others don’t? And what does that mean for their long-term outcomes?

A new study delves into this question by examining essays written by 11-year-old girls back in 1969. These essays, combined with data about their authors’ subsequent home lives and careers, provide a unique opportunity to explore individuals’ conformity to gender norms and the impacts on their lifetime earnings.

"With innovative techniques, we measured how much girls conform to gender norms and linked it to their later life outcomes."

The essays

The research uses a unique dataset: over 10,000 essays by 11-year-olds in 1969. The essays were written by participants of the National Child Development Study (NCDS), initiated in 1958. Since its inception, the NCDS has meticulously tracked these individuals from birth to the present day, offering valuable insights into various aspects of their lives. The essay examined in this study asked the children to write about what kind of life they imagined leading at 25 years old including hobbies, work and home life.

The essay question, which 11-year-old girls responded to in 1969.

The essay question, which 11-year-old girls responded to in 1969.

"The essay variety is fascinating. Some girls write about housework and waiting for their husbands to return from work. Others write about becoming space engineers and taking holidays in New York"

Machine learning

The project used machine learning and text analysis to examine the 1969 essays and establish how far each girl’s views on gender roles conformed to societal norms.

The research team utilised an algorithm originally developed by Google and trained on Google News data to understand the meanings and associations of different words. Since word associations change over time, the algorithm was re-trained using over a million books written between 1958 and 1978 to align with when the essays were written.

A gender association score was assigned to each word, based on its typical association with either males or females at that time. This enabled the team to effectively understand and evaluate the gender dynamics within each essay.

“The toughest part of this research was figuring out how to extract conformity with gender norms from the essays.”

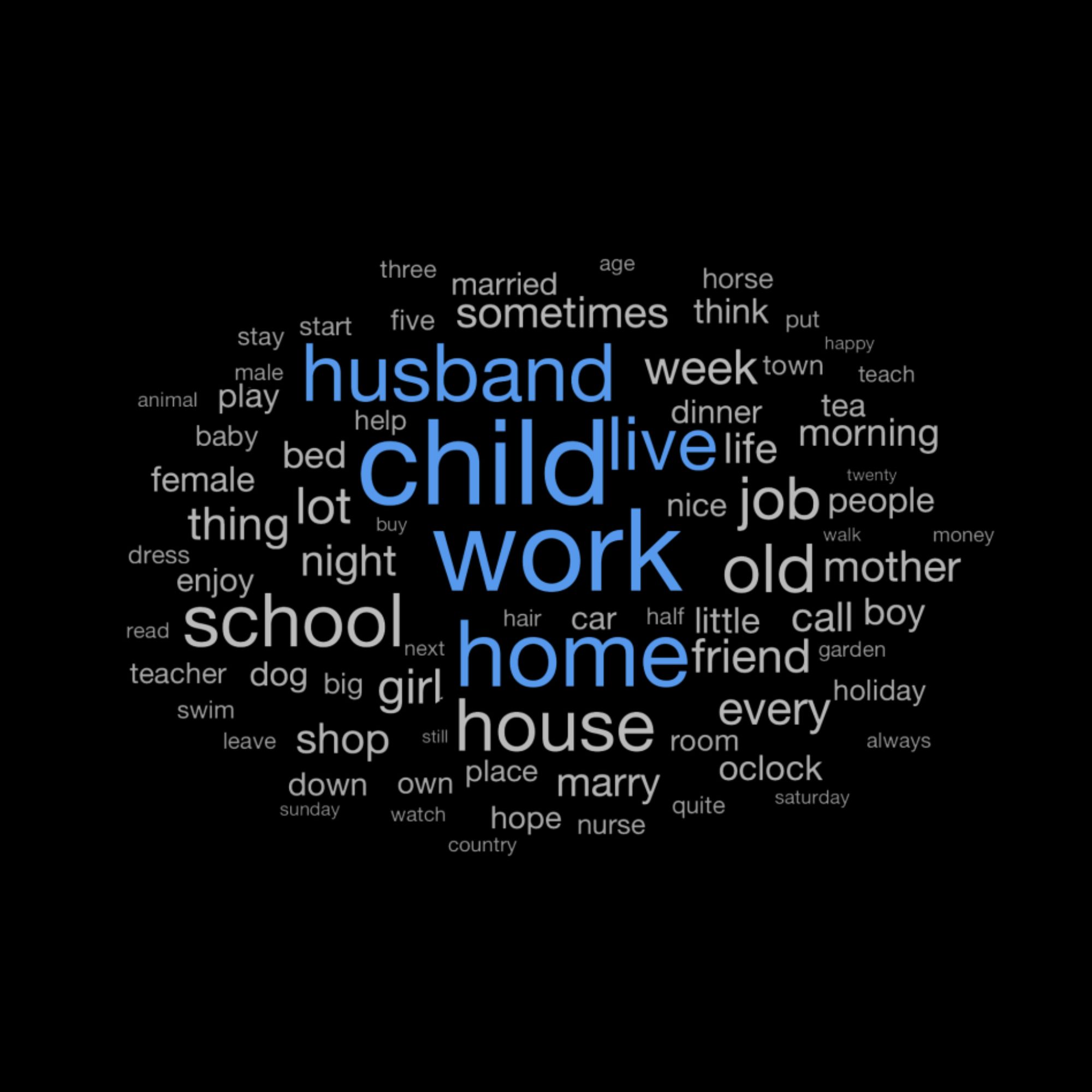

Word cloud showing frequently used words in the essays.

Word cloud showing frequently used words in the essays.

Research impact

The research finds that girls who conform more with traditional gender norms tend to attain less education, get married and have children earlier, as well as choose lower paid occupations.

Even controlling for other important variables such as cognitive skills, socio-emotional skills, family income and more, the project finds there are large differences in girls’ conformity with gender norms early in life and that they have an impact on later life outcomes.

Establishing this direct link is crucial for promoting gender equality and creating a more equitable society. It shows that if we develop targeted interventions to empower girls to defy traditional gender roles, in schools and other early-years environments for example, we are likely to create a positive impact on their later life outcomes and earnings.

Watch the video

Dr Uta Bolt

Uta Bolt is an Assistant Professor (Lecturer) in Economics at the University of Bristol, and a Research Associate at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. She is one of the researchers on the project, along with Sreevidya Ayyar, Eric French and Cormac O’Dea. Read the full paper here.

Uta’s research interests include human capital development, gender, health economics and inequality.

“I was drawn to this study because gender conformity greatly influences women's work decisions, yet it's hard to measure. I wanted to bridge this gap.”